Learning to love the hard truths

What happens when we sanitize our most difficult histories? A powerful essay about Oklahoma offers lessons for struggling with painful pasts.

Oklahoma's legacy and W&L's reckoning Problem

In a poweerful essay in The Guardian, Caleb Gayle explores how he learned to love Oklahoma: He does so not despite its violent history, but because of his willingness to confront it. His recounts his journey. As a Black child, he reenacted land runs in school. Now as an adult scholar, he's traced buried stories of Black sovereignty. This can offer a profound insight for our University. It has continued to struggle with meaningful historical reckoning.

Other institutions in state, UVA and William & Mary have met this in a much more head on way.

William & Mary even puts it front and center, very near the Wren Building, the foundational heart of the campus.

The sanitization problem

Gayle's childhood experience is haunting: fourth-graders equipped with wagons and stakes, racing across a schoolyard to claim "their" land in a cheerful reenactment of the land runs that dispossessed Indigenous peoples. Oklahoma's public schools didn't ban these exercises until 2014. The schools replaced them with, "a sanitized, feel-good version of state history."

This sanitization isn't unique to Oklahoma's elementary schools. At the University of Oklahoma, crowds still chant "Boomer! Sooner!"—celebrating the very settlers and cheaters whose "pioneering spirit" was built on "theft and violence." The university's mascot remains a covered wagon, an emblem of dispossession transformed into school pride.

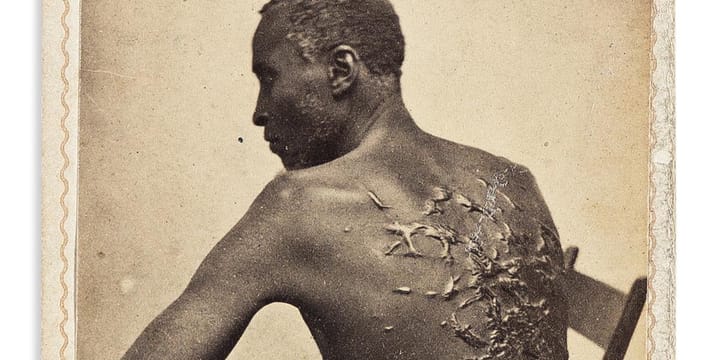

Washington and Lee faces a strikingly parallel challenge. Despite removing Confederate flags and adding contextualization, it still bear the name of a slaveholder who committed treason. Like Oklahoma's "Boomer Sooner" chant, the name represents more than historical acknowledgment—they actively celebrate figures whose legacies are inseparable from systems of oppression.

The University still remains the country's largest Confederate memorial. Hiding the Recumbent Lee statue is only a baby step.

The deeper threat of true reckoning

Gayle's then relates the story of Edward McCabe. And how it reveals why authentic historical reckoning feels so threatening. McCabe, the first Black statewide elected official in the old West, envisioned something radical: a Black-governed state where African Americans could live "unmolested by the selfish greed of the white man." His dream wasn't just about survival—it was about sovereignty, self-determination, and belonging on Black people's own terms.

That vision was "mocked, sabotaged and eventually erased from civic memory" because, as t represented "not just a land grab, but a claim to belong. A declaration of autonomy."

Universities face similar fears when confronted with calls for genuine transformation. True reckoning with institutional histories of slavery, segregation, and exclusion inevitably raises uncomfortable questions about power, belonging, and who gets to define institutional identity.

It's far easier to add a plaque or change the name of a building than to fundamentally reimagine how an institution understands itself.

Why cosmetic change isn't enough

Gayle describes Oklahoma's current reinvention strategy: courting artists, remote workers, and digital nomads with financial incentives while asking "far less of itself when it comes to honoring the people and histories already here." The result brings headlines but "rarely brings healing."

Higher education's approach to historical reckoning often follows a similar pattern. Name changes, diversity initiatives, and Land Acknowledgments can become performative gestures that allow institutions to claim progress while avoiding deeper structural changes. The decision to keep Lee's name while adding "contextualization" exemplifies this approach—acknowledging discomfort without addressing its fundamental source.

The theology of place

Perhaps most powerfully, Gayle argues that "place matters. Not just as geography, but as some kind of theology." The physical spaces we inhabit and celebrate carry moral weight. When universities maintain buildings, traditions, and naming conventions that honor those who perpetrated historical violence, they're making theological statements about whose lives and dreams matter.

McCabe understood this. His vision of Black sovereignty wasn't just political—it was sacred, an attempt to create sanctified ground where Black belonging could flourish without white oversight. Though his dream was violently suppressed, the 13 all-Black towns that remain in Oklahoma (down from 50) still testify to the possibility of spaces organized around different values.

Learning to love hard truths

What makes Gayle's essay so compelling is his insistence that love and pride can coexist with historical honesty. His affection for Oklahoma doesn't come from its "polished reinvention" but from "the hard work of seeing my state clearly, in all its contradictions: the violence and the love, the buried history and the stubborn hope."

This mirrors why we care so much about change at the University. It transformed my life and many others'.

It also offers a model for universities wrestling with difficult legacies. Rather than sanitizing or minimizing historical violence, institutions could find their strength in unflinching examination of how they've participated in systems of oppression—and how they might participate in repair.

For Washington and Lee, this might mean moving beyond the current compromise of keeping Lee's name while adding context. True reckoning would require asking harder questions: What would it mean to organize the university around different values? How might the institution honor those who suffered under the systems that Lee (i.e., chattel slavery)? What would true inclusion look like for communities that have been historically exclude

Only by confronting the full truth of institutional histories can universities begin to imagine what genuine transformation might look like.

Non in cautus futuri.