The fight for fair representation: understanding what’s at stake in Louisiana v. Callais

Louisiana v Callais could roll back what remains of the Voting Rights Act, putting the future of America’s multiracial democracy at stake

On 15 October 2025, the Supreme Court will hear Louisiana v. Callais, which could reshape not just Louisiana's congressional map, but the future of the Voting Rights Act itself. It could change how race can be considered in all redistricting moving forward. As legal scholar Leah Litman writes in The Guardian, this case represents the culmimation of a 160-year-old campaign against civil rights. In short, the case threatens the future of multiracial democracy in the U.S.

The backdrop for this case

The case asks whether Louisiana lawmakers properly balanced constitutional protections and Voting Rights Act requirements when they created a congressional map in 2024. This map includes two districts with Black majorities. Black Louisianians are one-third of the state's population, and they have advocated for fair representation in Congress for years using all the tools avaialble to them.

The Supreme Court will determine if states can consider race when drawing districts to remedy discrimination or if such considerations violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The road to an equitable map and an immediate challenge

This story begins after the 2020 census. Based on it, Louisiana's legislature drew a congressional map in 2021 that had only one majority-Black district. Despite Black residents comprising a third of Louisiana's population, the map gave them the opportunity to elect only one-sixth of the state's congressional representatives. Thus, it significantly diluted their voting power compared to white voters.

Black voters and civil rights organizations, represented by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), challenged this map as a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. This prohibits voting policies that in effect disadvantage Black voters. This section of the act addresses s long history of disenfranchisement.

Multiple federal courts agreed. They found the original map likely violated the Voting Rights Act by weakening Black voters' political power. The courts ordered Louisiana to redraw the map by January 2024 to include a second majority-Black district where Black voters would have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

In January 2024, the legislature passed a new map, known as SB 8, to create a second majority-Black district. It connected communities from Baton Rouge north along the Red River through Alexandria to Shreveport. Legislators cited political priorities for this configuration, including protecting the incumbency of powerful Louisiana congressmembers like Republican Speaker of the House Mike Johnson. Of course, no powerful white politician would be potentially harmed.

Shortly after SB 8 became law, a group of white voters filed a new lawsuit that challenged it as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Their theory was ludicrous. They argued that the legislature discriminated against whites. (It denied them outsized representation of the original map).

A divided three-judge federal panel sided with these challengers and struck down the map, finding that it violated the Equal Protection Clause. This created a remarkable legal conundrum. federal courts first required Louisiana to create a second majority-Black district to comply with the Voting Rights Act, then they struck down that very map as unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court weighs in

Both Louisiana and the Black voters from the original case appealed to the Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in March 2025. Rather than issuing a decision by the end of its spring term, the Court took the unusual step of ordering the case to be reargued in the fall with a narrower focus.

The Court's reargument order asked parties to address a fundamental question: Does the intentional creation of a majority-minority district as a remedy for vote dilution found by a court under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act violate either the 14th or 15th Amendments?

This question strikes at the heart of voting rights law. If the answer is yes, it could make it nearly impossible for states to remedy voting discrimination without simultaneously violating the Constitution.

Legal experts say the Court's decision to reargue the case suggests deep debate among the justices about a potential major shift in voting rights jurisprudence.

Louisiana reverses course

In a supplemental brief filed in August 2025, Louisiana took a surprisingly broad position, arguing that all "race-based redistricting is unconstitutional."

This represents a significant shift from the state's original defense of its redrawn map and suggests Louisiana now believes that complying with the Voting Rights Act itself may be unconstitutional.

Or, they are just seeing which way the wind tends to be blowing (like everyone else).

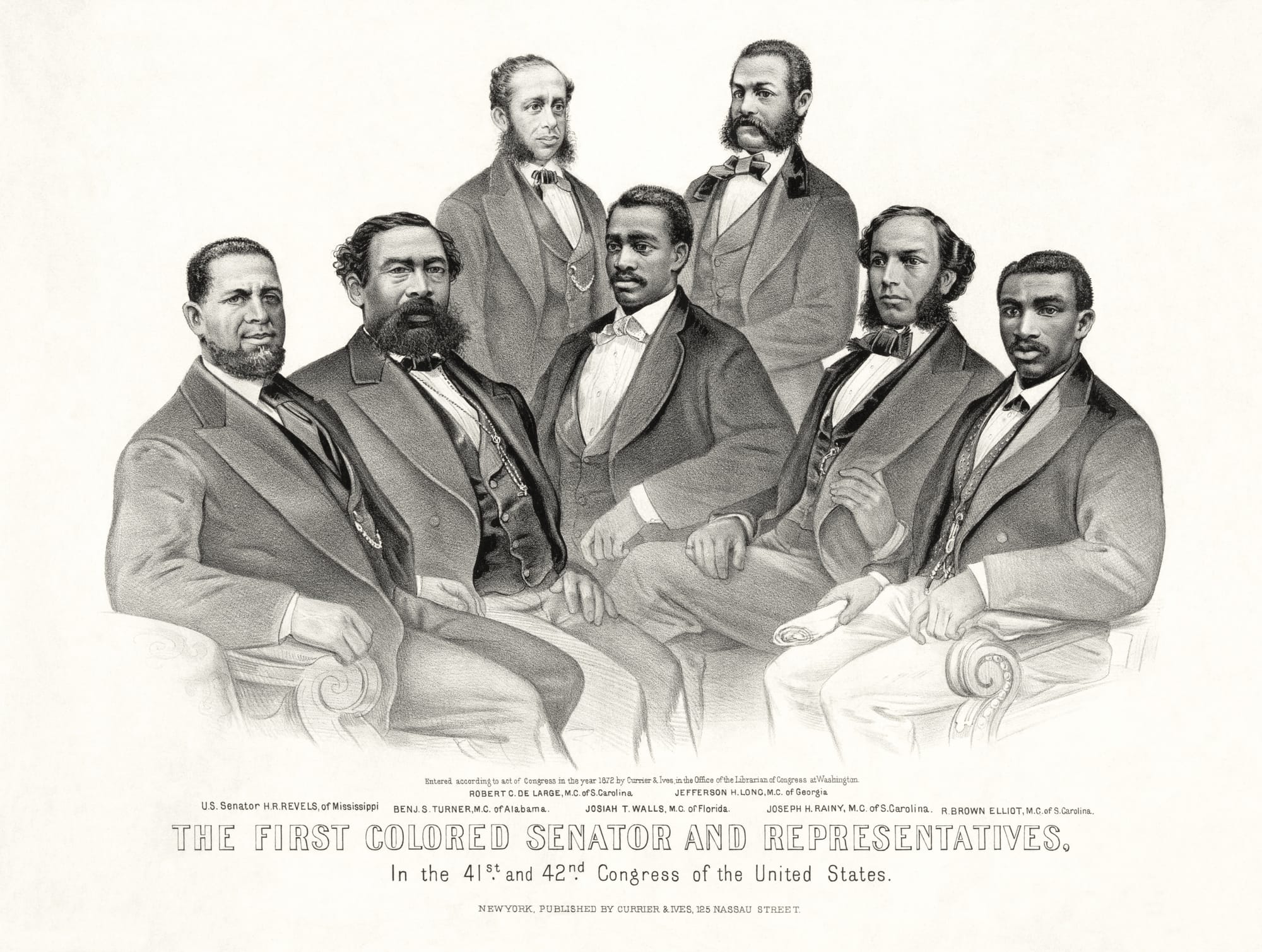

A 160-year battle over reconstruction

As The Guardian's analysis notes, Louisiana v. Callais is about far more than redistricting—it's part of a broad effort to reinterpret the Reconstruction amendments and either ignore them outright or even weaponize them against democracy and civil rights. The case lies on a straight line from a campaign that began immediately after the Civil War.

The Reconstruction era, following the end of slavery, sought to integrate Black Americans into the political system and protect their rights. This included passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, which outlawed slavery, guaranteed equal protection, and prohibited racial discrimination in voting. As Senator John F. Edmunds said in 1869, the 15th Amendment would allow Black voters "to choose from among his fellow citizens the man who suits him for his representative."

Reconstruction initially produced real gains. Within years, former Confederate states sent Black representatives and senators to Congress and elected Black leaders to state offices.

This real progress, however, was short lived. It was met with virulent racism and violent resistance, including the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

The anti-Reconstruction movement used language that sounds familiar today:

- Federal civil rights protections were too radical

- Protections were no longer needed since slavery had ended (we live in a post racial society anyone because Obama anyone?)

- Protecting Black citizens was actually unfair discrimination against white people

When Andrew Johnson, covering himself in his usual glory, vetoed a congressional civil rights statute, he insisted it "operated in favor of the colored and against the white race."

The Supreme Court echoed this logic in 1883 when it invalidated the Reconstruction-era Civil Rights Act, declaring that freedmen should "cease to be the special favorite of the laws."

In short, opponents tried to weaponize the principles of Reconstruction against itself—arguing that prohibiting discrimination against Black Americans was itself discrimination against would-be discriminators.

This logic has endured through the decades and now appears in Louisiana v. Callais, where white voters claim that ensuring fair representation for both Black and white voters somehow discriminates against white people.

Why whites always think equality is like a pie eludes me. The only rigthtrs they lose are those to discriminate and subjugate.

Why Section 2 matters

The Brennan Center for Justice filed a friend-of-the-court brief highlighting the transformational impact that Section 2 vote-dilution claims have had since the 1980s. Nearly half of all Section 2 cases since 1982 have challenged at-large elections by cities, school districts, counties, and other local governments.

These cases resulted in hundreds of jurisdictions moving to fairer electoral systems over four decades, dramatically expanding representation for voters of color, especially, but not only, in the South.

The brief argues that Section 2 is a carefully tailored tool with demanding requirements. Under the framework established in Thornburg v. Gingles, plaintiffs must prove the existence of racially polarized voting so severe that the normal give-and-take of politics is no longer possible for voters of color. The law is not a mandate for universal race-based districting, but rather a targeted remedy for the most racially divided communities.

Nationwide impact

The NAACP's LDF has emphasized that this case goes beyond just maps—it's about the future of multiracial democracy in the U.a. It's about ensuring that every vote counts. Fair representation in Congress can lead to real improvements in health care access, education, environmental safety, infrastructure, and other issues that directly affect communities.

The reargument itself signals the case's significance. As LDF notes, some of the Supreme Court's most consequential decisions, including Brown v. Board of Education, came following reargument. The Court's decision to hold the case over suggests the justices recognize the profound implications of their eventual ruling.

If the Supreme Court sides with the challengers and finds that remedying vote dilution violates the Constitution, it would gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and make it almost impossible to address racial discrimination in redistricting.

This would allow the Republican party to engage in even more partisan gerrymandering that it does today. The goal would be elimination several legislative districts held by Democratic officials, many of whom are racial minorities.

If the Court sides the Black voters defending the map, it would affirm that states can and must consider race to ensure equal political opportunities for all citizens—preserving a key protection from the civil rights movement.

Ideals versus our reality

The Guardian piece places this case in the troubling context of America's current democratic health, or lack thereof. With an executive branch wielding unprecedented power, a legislature failing to check that power, and a Supreme Court that has largely rubber-stamped the administration's novel assertions of authority, the future of voting rights protections appears increasingly precarious—if not outright doomed.

The Supreme Court has already allowed the executive branch to engage in racial profiling through roving immigration patrols, to fire non-regime friendly officials in violation of federal law, and to dismantle entire departments.

Louisiana v. Callais represents the Court's potential participation in a far-reaching rightwing project that stretches back to the end of the Civil War. And further would move the clock backward to Jim Crow America.

What happens next

The case is scheduled for oral reargument on 15 October. The current map with two majority-Black districts remains in place pending the Court's decision. Nationwide, voting rights advocates, state legislators, and legal scholars will be observing it closely. They know the Court's ruling will shape the future of our democracy for generations.

Black Louisianians have spent years fighting for fair maps—from their communities all the way to the Supreme Court. To them, the case represents both the culmination of their efforts and a porential death blow in their ongoing struggle for equal political power.

Will the promise of Reconstruction be reaffirmed or dismantled.

Non in cautus futuri.